Quiet exploitation: Foreign health and care workers in the UK forced into silence for visas

The Bureau for Investigative Journalism and Citizens Advice in the UK documented more than 150 migrant health and care workers facing abuse or exploitation but remained silent to protect visa-sponsored jobs. The actual number is likely higher.

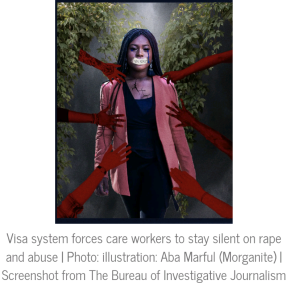

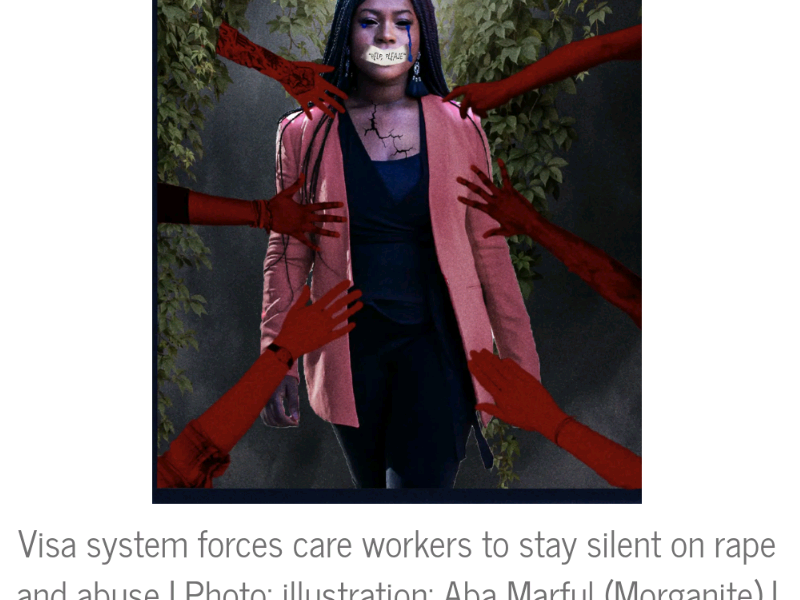

Hundreds of foreign health and care workers who have experienced sexual abuse and exploitation are trapped in silence, in fear of losing their work rights, an investigation by The Bureau for Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) revealed.

TBIJ, together with the charity group Citizens Advice, collected testimonies from over 175 people working for 80 care providers under Britain’s health and care worker visa. The actual number is likely to be higher.

Accounts of the workers include that of Bernice*, from the Caribbean, who alleged she was sexually harassed by her landlord in the accommodation arranged by her employer. Her employer sponsored her work permit in the UK.

One live-in carer was threatened with dismissal and visa revocation when she complained about being forced to work an exhausting 20 hours a day.

Another worker, Abena* from southern Africa worked for a care home. She told Citizens Advice that her boss raped her on several occasions. She sought help from a rape crisis center but not the police. She told her boss to keep their relationship “purely professional”. He stopped giving her shifts, which Abena believes was retaliation for her rejection.

Citizens Advice began noticing an increase in calls from people in the health and care work industry last year. In their calls to the Citizens Advice hotline and interviews with TBIJ, care workers detailed instances of wage theft, illegal recruitment fees reaching £30,000, unfulfilled promised hours, and being on the brink of poverty due to adverse working conditions in the care sector. Many were “already in debt and unable to pay for food, rent, and other bills,” TBIJ reported.

Because of the conditions stipulated under the UK healthcare worker visa, the distressed workers had “no recourse to public funds” and could not claim most benefits or help with housing.

Totally dependent on the employer

The investigation underscores the gaps in the UK’s visa system for health and care workers, which renders individuals entirely dependent on their employers.

According to UK government data, a total of 121,290 Health and Care Workers Visas were issued in 2023, marking a 157% increase over the previous year. In 2022, 47,194 were issued.

The UK Health and Care Worker Visa, introduced in 2020, is a visa category designed to facilitate the entry of healthcare professionals into the UK. Doctors, nurses, health professionals, or adult social care professionals are included in the list of qualified occupations.

According to a report by the Health Foundation, the UK needs an estimated 122,000 more healthcare workers by 2030 to meet the needs of its population. The shortage of healthcare workers in the UK, further exacerbated by Brexit, has left the UK scrambling to recruit foreign workers to fill these essential roles.

To qualify for the health and care worker visa, an applicant must have a job offer from an approved UK employer, also known as a sponsor.

On paper, the linkage to employers is intended to ensure that health workers have employment upon arrival and to regulate the flow of migrant workers into the healthcare sector. In practice, however, the provisions of the visa create a significant employer dependency.

This places employers in an “incredible position of power”, Dora-Olivia Vicol, chief executive of the Work Rights Centre, an organization that supports migrant workers told TBIJ.

Trapped on all sides

Healthcare workers face compounded restrictions under their visa regulations. They are tied to their employer and cannot access public funds if they leave their job. If they quit, they have only 60 days to secure new employment, which is challenging when housing is provided by the employer. Additionally, some have contracts with “clawback” clauses that require them to repay recruitment fees if they resign.

“There are potentially thousands of people trapped in a system that leaves them vulnerable to abuse and threats, powerless to complain, and often losing thousands of pounds,” Kayley Hignell, the interim director of policy at Citizens Advice, told the British newspaper The Guardian. “These people are skilled professionals who keep our healthcare services running yet are left without a safety net when things go wrong.”